Dierlijke uitdagingen overwinnen

Sluiting van Boudewijn Seapark: een einde aan dolfijnengevangenschap

Het dolfinarium van Boudewijn Seapark wordt bekritiseerd vanwege de ontoereikende ruimte en volume, wat leidt tot diverse welzijnsproblemen voor dolfijnen. Deze problemen omvatten een gebrek aan omgevingsstimulatie, onnatuurlijk gedrag en gezondheidskwesties. Als optimale oplossing wordt voorgesteld de dolfijnen te verplaatsen naar reservaten zoals het Aegean Marine Life Sanctuary in Griekenland, waar ze een meer natuurlijke leefomgeving kunnen genieten.

Een alternatieve aanpak betreft het aanpassen van de Vlaamse wetgeving om een kweekverbod in te stellen voor de dolfijnen in Boudewijn Seapark, wat uiteindelijk tot de sluiting van het dolfinarium zou leiden. Beide scenario’s zouden een aanzienlijke positieve impact hebben op het welzijn van de dolfijnen, met verbeteringen in zowel hun fysieke als mentale gezondheid. Hierbij moet wel rekening worden gehouden met mogelijke stress door veranderingen in omgeving en sociale structuur.

Hoewel er potentiële kortetermijnnadelen zijn, zijn wij ervan overtuigd dat de langetermijnvoordelen van het beëindigen van dolfijnengevangenschap ruimschoots opwegen tegen deze tijdelijke uitdagingen.

Ontoereikende leefruimte voor dolfijnen in Boudewijn Seapark

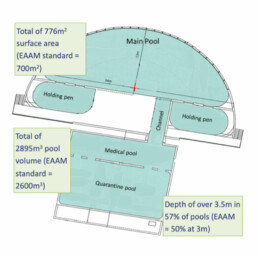

De zeven dolfijnen in Boudewijn Seapark leven in een beperkte ruimte. Met een totale oppervlakte van 776 m² en een volume van 2.895 m³ is hun leefomgeving aanzienlijk kleiner dan wat als optimaal wordt beschouwd. [1]

Hoofdbassin

Bassin aan de achterkant

Plattegrond van het dolfinarium

Een officiële Dolfijnenstudie, in opdracht van de Vlaamse Regering (2021/2022) bevestigt deze bevinding: [2]

‘(…) het zwembadvolume per dolfijn in Boudewijn Seapark (362m³*/dolfijn) valt momenteel in de categorie “suboptimaal” wat betreft welzijnseffecten, en om de beste welzijnsscore te bereiken zouden ze meer dan 700m³/dolfijn moeten bieden (…)’

Om dit in perspectief te plaatsen: momenteel heeft elke dolfijn een ruimte vergelijkbaar met een kubus van 7,1 meter aan elke zijde. De aanbevolen ‘optimale’ ruimte zou overeenkomen met een kubus van 8,9 meter – nog steeds beperkt, maar een verbetering.

Echter, zelfs deze ‘optimale’ ruimte in gevangenschap valt in het niet bij de natuurlijke leefomgeving van dolfijnen. In het wild kunnen tuimelaars dagelijks afstanden tot 160 kilometer afleggen, met snelheden tot 30 km per uur.[3] Dit scherpe contrast tussen het natuurlijke habitat en gevangenschap onderstreept hoe zelfs verbeterde omstandigheden in dolfinariums ver achterblijven in vergelijking met wat dolfijnen in het wild ervaren.

Welzijnsproblemen van dolfijnen in gevangenschap

De Dolfijnenstudie identificeert diverse welzijnsproblemen voor de zeven dolfijnen in Boudewijn Seapark:

- Ontoereikend bassinvolume

- Gebrek aan omgevingsprikkels, resulterend in suboptimaal gedrag

- Verminderde sociale interacties bij vijf van de acht dolfijnen

- Suboptimale relaties tussen dolfijnen en trainers buiten voedingsmomenten

- Dagelijkse frustratie door opsluiting in kleine wachtruimtes tussen trainingen

- Onvoldoende interactie met verrijkingsmateriaal bij vier dolfijnen

Naast deze specifieke kwesties zijn er inherente welzijnsproblemen in dolfinariums zoals Boudewijn Seapark:

- Kunstmatige leefomgeving: het leven in een onnatuurlijke habitat kan leiden tot gezondheidsproblemen zoals oogaandoeningen door chemisch behandeld water.[4]

- Geluidsoverlast: d econstante blootstelling aan luide muziek en geluiden van pompen en filters veroorzaakt stress bij deze geluidsgevoelige dieren.[5]

- Beperkte bewegingsvrijheid: De beperkte ruimte kan leiden tot abnormaal gedrag en agressie.[6]

- Controversiële trainingsmethoden: het gebruik van voedselrestrictie tijdens training kan leiden tot verhoogde stressniveaus.[7]

- Gezondheidsrisico’s: Ondanks verbeterde veterinaire zorg, vertonen dolfijnen in gevangeschap vaak stress-gerelateerde aandoeningen en zijn ze vatbaarder voor vroegtijdig overlijden door infecties of andere gezondheidsproblemen. [8]

Ideale toekomst voor dolfijnen in Boudewijn Seapark

Een optimaal scenario voor de dolfijnen uit het Boudewijn Seapark Dolfinarium zou hun verhuizing naar een natuurlijk reservaat zijn. Deze overgang zou hun welzijn aanzienlijk verbeteren door hen een omgeving te bieden die veel dichter bij hun natuurlijke habitat ligt. Om deze doelstelling te realiseren, is het van essentieel belang dat de Vlaamse Minister van Dierenwelzijn proactief het initiatief neemt in onderhandelingen over de voorwaarden en praktische aspecten van zo’n verhuizing.

Uit de Dolfijnenstudie zijn zeven potentiële reservaten naar voren gekomen die geschikt zouden zijn voor de dolfijnen van het Boudewijn Seapark. Enkele opties zijn:

- Het Aegean Marine Life Sanctuary in Griekenland, momenteel in ontwikkeling met steun van de Universiteit van Toronto en World Animal Protection.

- Het Umah Lumbah Centre in Italië en Kreta, dat al twee heiligdommen heeft geopend.

- Het National Aquarium Baltimore’s Dolphin Sanctuary Project, dat mogelijk vanaf medio 2026 dolfijnen kan verwelkomen.

Hieronder vindt u een impressie van het leven van dolfijnen in het Aegean Marine Life Sanctuary (AMLS) in Griekenland, een van de potentiële nieuwe thuishavens:

Een verhuizing naar een reservaat zou de dolfijnen van het Boudewijn Seapark de unieke kans bieden om in een omgeving te leven die hun natuurlijke leefgebied nabootst. Deze overgang zou niet alleen hun fysieke gezondheid bevorderen, maar ook hun mentale welzijn aanzienlijk verbeteren. In een ruimere, meer natuurlijke omgeving zouden de dolfijnen de mogelijkheid krijgen om een rijker en meer vervullend leven te leiden, wat hun algehele levenskwaliteit drastisch zou verhogen.

Alternatief scenario

Een alternatief scenario betreft het aanpassen van de huidige Vlaamse wetgeving. Hoewel deze wetgeving dolfinaria verbiedt, maakt ze een uitzondering voor het Boudewijn Seapark Dolfinarium in Brugge. Het voorstel is om deze wetgeving aan te passen en een kweekverbod op te leggen voor de zeven dolfijnen in het Boudewijn Seapark. Dit kweekverbod zou onderdeel zijn van een bredere uitfaseringsstrategie, met als uiteindelijk doel de sluiting van het dolfinarium na het natuurlijke overlijden van de huidige dolfijnenpopulatie.

OSTA’s standpunt contrasteert met de Dolfijnenstudie [9], die suggereert dat een kweekverbod het dierenwelzijn negatief zou beïnvloeden en het bestaan van dolfinaria onnodig zou verlengen. OSTA stelt daarentegen dat een kweekverbod geen negatieve gevolgen heeft voor het welzijn van dolfijnen. Deze visie wordt ondersteund door ervaringen met kweekverboden in bestaande dierenreservaten, waar geen negatieve effecten op de dieren zijn waargenomen.

Bovendien betwist OSTA de veronderstelling dat dolfijnen aanzienlijk zouden lijden als ze niet zouden kunnen voortplanten. Dit argument is gebaseerd op de overtuiging dat reproductie niet essentieel is voor een betekenisvol leven. Hoewel uitgebreid onderzoek naar de langetermijneffecten van kweekverboden op dierenwelzijn beperkt is, wijzen bestaande studies, die zich voornamelijk richten op korte-termijn gezondheidseffecten, erop dat een kweekverbod verenigbaar kan zijn met een positieve welzijnstoestand bij dolfijnen.

Potentiële impact: een optimale realiteit voor dolfijnen

7 dieren

7 dolfijnen

__

In het Boudewijn Seapark Dolfinarium verblijven zeven dolfijnen: zes vrouwtjes en één mannetje. Deze intelligente zeedieren nemen dagelijks deel aan publieke trainingssessies.

De dolfijnen zijn:

- Vrouwtjes: Puck (~58 jaar), Linda (~48 jaar), Roxanne (~38 jaar), Yotta (~25 jaar), Indy (~21 jaar) en Moana (~9 jaar).

- Mannetje: Kite (~18 jaar).

Het verbeteren van het welzijn van deze zeven dolfijnen en hun mogelijke nakomelingen vereist twee cruciale stappen: verplaatsing naar een reservaat en invoering van een kweekverbod.

Een reservaat biedt een ruimere, meer natuurlijkere omgeving die de fysieke en mentale gezondheid van de dolfijnen bevordert. Hoewel een verhuizing initieel stress kan veroorzaken door veranderingen in omgeving en sociale structuren, overtreffen de langetermijnvoordelen ruimschoots deze tijdelijke uitdagingen.

Een kweekverbod is een essentiële stap naar het uitfaseren van dolfijnengevangenschap. Ondanks mogelijke kortstondige verstoringen in gedrag en sociale dynamiek, draagt dit verbod uiteindelijk bij aan een verbetering van het algehele welzijn. Bovendien voorkomt het de geboorte van nieuwe dolfijnen in gevangenschap, wat een einde maakt aan deze omstreden praktijk.

[1] Foto’s en plannen zijn afkomstig uit het ‘Advies van de Raad voor Dierenwelzijn in België, Beschouwingen over het houden van dolfijnen (*Tursiops truncatus*) in dolfinaria’ (wetenschappelijk rapport, 2010) en de ‘Study on keeping dolphins in captivity (‘Dolfijnenstudie’)’, geschreven door Dr. Isabella Clegg van Animal Welfare Expertise, in april 2021.

[2] Voor meer details, zie de Dolfijnenstudie, Studie 1, Welzijnsstudie, 31.

[3] Ocean Conservancy, ‘Tuimelaar’ <https://oceanconservancy.org/wildlife-factsheet/bottlenose-dolphin>.

[4] C. Colitz, M. Walsh, en S. McCulloch hebben in hun studie ‘Characterization of Anterior Segment Ophthalmologic Lesions identified in Free-Ranging Dolphins and those under Human Care’ (2016, Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 47: 56-75) oogaandoeningen bij dolfijnen onderzocht. De Dolfijnenstudie, Welfare study (Study 1, 26) vermeldt specifiek dattwee dolfijnen in het Boudewijn Seaparkoogaandoeningen hebben.

[5] L. Couquiaud, Special Issue: Survey of Cetaceans in Captive Care (2005) 31/3 Aquatic Mammals 277-385.

[6] R. Clubb and G.J. Mason, ‘Animal Welfare: Captivity Effects on Wide-Ranging Carnivores’ (2003) 425 Nature 473-474.

[7] N. Stewart, ‘Dolphins in Captivity Endure Seven Stages of Suffering in Their Tragic Lives,’ World Animal Protection, April 14, 2021.

[8] L. Marino et al., ‘The Harmful Effects of Captivity and Chronic Stress on the Well-being of Orcas’ (2019) 35 Journal of Veterinary Behavior 69-82.

[9] Ibid. Dolfijnenstudie (n2) Studie 1, Welzijnsstudie, 37-38.